Whenever I think about those miners who went down or still go down into underground mines, I can’t fathom how they do it. My maternal grandfather was an underground miner and my Mother used to say, when thinking back on her father’s work, “Someone owes us a lot of money.” Those men were paid so little for such dangerous, hard labor.

To celebrate Ely’s 100th birthday in 1988, The Ely Echo Newspaper published a wonderful book called “Ely, Since 1888” that gathered stories and pictures about the historic area. There are many gems in the book and one of these is titled “Rescuers Free Trapped Ely Miner.” The story had originally been published in the Duluth News Tribune on January 23, 1960.

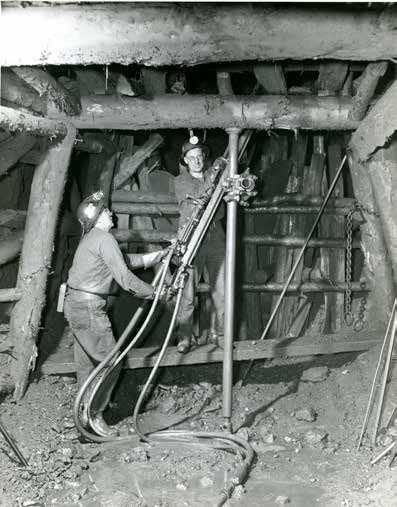

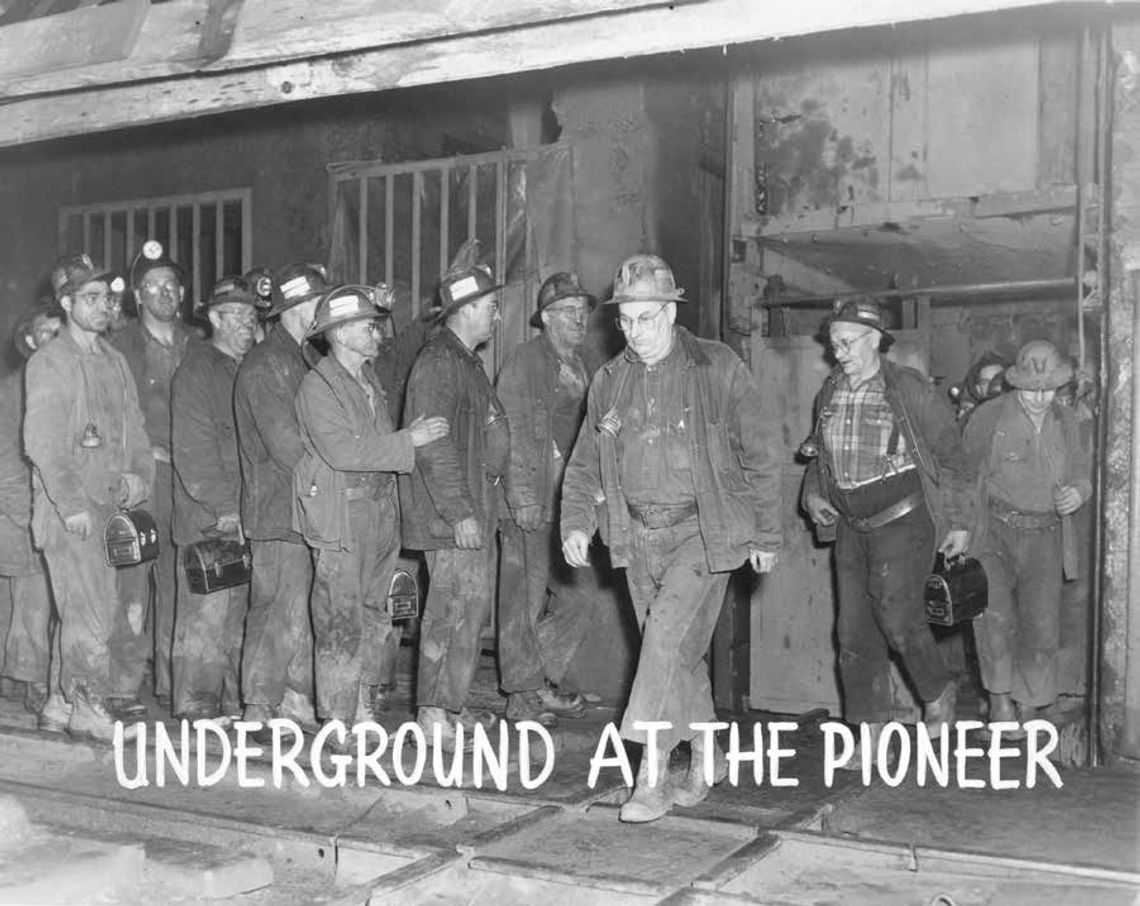

Come with the miners now, as they go “down the mine.”

A miner in the Pioneer iron ore mine in Ely was rescued at 11:30 p.m. yesterday after he had been trapped by a mud flow 1,500 feet below ground for about 15 hours.

Reported in good condition, although he had been without food and water since early morning, was Joseph Mishmash, 50, a miner for 33 years.

Mishmash was given a cup of coffee in the underground office of the mine captain before being taken to the surface.

He and his working partner, John Koski, 55, leaped for safety in opposite directions when, without warning, mud broke into their working area in a raise (a vertical shaft within the mine).

The tons of mud, a mixture of fine soil, rocks, and debris, welled up between the men. A mine official said Mishmash leaped towards a drift (a horizontal or gently sloping tunnel which serves as a passageway. They are the primary “roads” of the underground mine.) Mishmash was thus trapped behind the rising mud, while Koski escaped by swiftly climbing up the raise.

The partners were installing cribbing, the large wooden bracing timbers within the mine, at the time of the accident. They were working between the 15th and 16th levels of the mine.

The rescue workers were immediately on the scene, ready to reach their trapped colleague. The rescuers had to drill through about 15 feet of ore before they could reach the trapped man. Mishmash awaited rescue in an area about 40 feet long, 10 feet wide, and eight feet high.

Operations to remove the tons of iron ore between him and safety were delayed for a time while an iron pipe was driven through the debris to establish communication between the trapped miner and the rescue workers. The rescuers worked about 5 ½ hours to establish communications with him.

The drilling commenced with two crews of trained rescue workers alternating in their work. There were four men on each crew. The progress was slow because of the density of the ore and because the mudslide had carried heavy hardwood planks and other timbers used in the mining operations into the raise and drift. Jammed into the area and surrounded by mud, clearing the plugged area took time and skill.

Rescue workers occasionally touched off small charges of dynamite in order to clear the rubble. From time to time the crewmen shouted through the ¾-inch pipe to Mishmash and listened for his reply. “Everything’s okay,” was his reassuring call back to the rescuers. He was cautioned to stay away from the blast area and to report when his area became too smoky.

Meanwhile, as word of the trapped miner spread through the community, people congregated to await word of progress in the rescue operations. Many people received first word about the situation when they were called by others on prayer chains or school notification call chains. They were all asked to add their prayers for the safety of Joseph Mishmash and the men on the recue team. The prayer chains also sent many people to their churches and to their neighbors. The community held its breath awaiting word.

As many as 30 persons at one time gathered at the Mishmash home in Ely. At first, Mrs. Mishmash remained cheerful and expressed confidence that her husband’s rescue would happen soon. Later, however, as the hours went by, the strain began to tell and she was put to bed under sedation. The couple have no children.

Mishmash, a contract miner, is himself a trained rescue worker. He helped in rescue work at a cave-in in the Pioneer Mine in 1955 when there was a cave-in at the 15th level. One miner died in that cave-in and two others were rescued.

“Joe knows rescue work is a slow process,” a mine official said.

Koski was one of the rescue workers on this recent accident. He was relieved of his rescue work that afternoon when the shift was changed. He still waited at the mine for news of his co-worker.

Work in other parts of the mine continued. About 450 men are employed on a three-shift basis.

Just before 11 p.m., the word came to the surface that Joseph Mishmash had been rescued and would soon be coming to the surface. After his 15 hours below, he was a happy and grateful miner as he thanked each of the members of the rescue crew. All of the miners had smiles of relief and joy as they heard the good news.

— T his second story comes from a book titled “Ready to Descend— The Journals of Matt Hallila Pelto— 1908 to 1913.” Matt was a young man of 27 when he left Finland to seek his fortune in America. His three brothers also came to America to work on Minnesota’s Iron Range. Two brothers would stay in America while eventually Matt and one other brother returned to Finland, having decided that hard work on a small family farm in Finland was a better life than the hard, dark, dirty work of the underground mines.

Matt kept a journal during his years in America. He added more from his memories after he returned to Finland. The journals were all written in Finnish. Years later, after his death, his relatives gave the journals to an American relative, Vienna Saari Maki. They believed that since his journals were all about what life was like as an underground miner in northern Minnesota at that time, his writings would be of more interest in America than in Finland. Vienna Maki translated the journals and in 2000 the book, a combination of the four journals, was published.

A reminder: in 1908, when Matt was working in the Pettit Underground Mine near Gilbert, there were no labor unions, no Workers’ Compensation, no Social Security. Safety on almost any job was left up to the individual worker. Matt Pelto’s journals gives us a detailed and clear-eyed view of what life was like when the mine owners had virtually no interest in anything beyond how much money they could make from the mine. Workers’ lives held little importance to most of the owners.

A miner who has at one time or another been forced to face death, against his own wishes, unable to escape, certainly knows what runs through his mind at that moment. But if a miner would not agree to work in the midst of such lurking dangers, then he would have to give up his job. Often, most of these dangers could be prevented, if there was enough time to make the necessary repairs. But when the pressure and terrible rush is constant, there is no time for safety first.

“It’s the ore that pays” is the capitalist’s daily saying. To that, the miner replies, “I am forced to try, come what may.”

When one has become accustomed to all these dangers and almost always come out right, he tries out his luck even in the worst places.

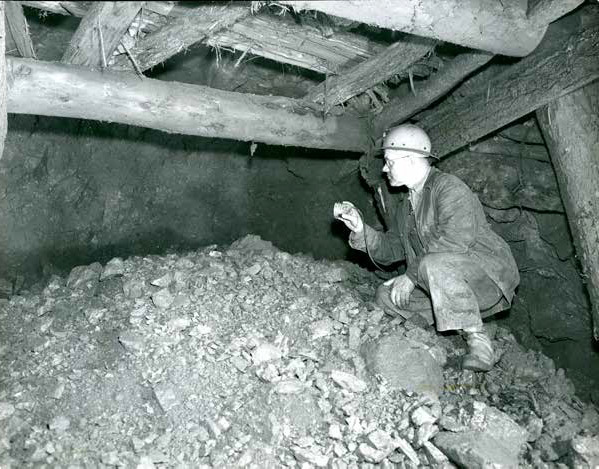

Once I was working with my brother in a new stope (a large underground excavation in a mine) into which a braced tunnel, also known as a raise, came straight up from the level below. There was almost enough room for us to begin to put up the first support timbers, called sets. The level directly above us had already been mined out. That ore had all been removed and blasting had been done to fill the place up with ordinary sand and rock. This fill had not yet reached all the spaces in the mined-out area.

The roof over our heads looked quite weak and rather threatening. Now and then small chunks of ore fell down, reminding us of the danger. The whole width of the room appeared to be sinking. But our workspace was too narrow, so we had to make more room for the posts by expanding to both sides. That was when the roof began to give way even more.

A large hanging chunk of ore loosened suddenly from the middle of the roof area and fell down right through our raise into the bottom level. In crashing through, it also broke some of our set-in timbers. We escaped injury by hugging an iron ore wall as close as we could. Above the hole now appeared an open underground space. It revealed a former back-level raise, similar to the one we were in now. It was hard to tell what condition it might have been left in, but the indications just then predicted disaster.

We got the spaces ready for each of the four 8-foot timbers and started to set them in their places. We had already hung the timbers up above. Gradually the fall of smaller chunks of ore seemed to lessen. After the posts were erected, a third timber or “cap” was raised above these. But first it was necessary to chop a space against the wall and the roof for this timber. That was always the most tiring and difficult job.

As soon as this activity started, the ore again began to dribble down. Dinnertime was approaching and so we didn’t have time to wait or linger. But as the falling ore began to worsen, it was necessary for us to think of means of escape, if the worst came to the worst.

This was the most trying dilemma we had ever come across in all our three years of working in this mine. We had two choices. We could give up our workplace or sacrifice our lives by continuing to work in that space.

We chose the latter, for if not us, someone else would be forced to do this work. It was a moment of great tension. Our hope was, as it had been so often before, that all would turn out for the best.

We worked on. Now the space for the timber cap was ready and we raised it into place. Yet that did not make it much more secure because the other end of the roof area was sagging very badly. As soon as we began to chop room for the next timber cap, our safety was threatened. I ordered my brother to hurry immediately to the opening to the bottom level, for there was that possibility now that both of us were in grave danger. “It is wrong for both of us to die here,” I said to him. “If it is my time to die, at least I will know that you are safe.”

One more time we glanced up at the impending danger and then my brother scurried down the raise to safety. I felt like one sentenced to die, there alone in my cell. Soon escape would be impossible in any direction.

I continued to work at placing the cap. The roof continued to sink. There was no time anymore to go down the opening. I pressed as close at the wall of ore as possible and watched the falling chunks come down, one after another. Some fell into the opening as well. Now the whole roof was cracking. The next instant the whole thing crashed down.

By instinct I turned to the wall, protecting my face with my hands. The candles in their wall holders and on my helmet snuffed out and then the whole terrible happening was almost over. I doubt that I had time to think during that moment. A thundering crash was happening right behind me. For a few seconds it left me in a stupor.

I came to when I heard my brother calling from below. He surely thought that I was crushed to death. But I called back to him that I was uninjured. After re-lighting my candle, I dared to look up again to see exactly what had happened.

I discovered that I had taken shelter in the right place, for on the opposite side of this room, the cave-in had come right up against the wall. I surely would have smothered.

I could see that there was now room above for our timber cap. My brother hurried up and we lifted the timber into place. Then we added a few more timbers directly beneath the timbers that remained from the upper level. Now we felt that the worst problems had been overcome. We had won.

This is one of those terrible moments I can never forget.