The Kingdom of Sweden was running low on money.

Constant battling with Norway, Denmark, Germany and Russia came close to depleting the treasury.

Sweden had control of the land to the east of the Gulf of Bothnia but only had a presence on the western shore of that land. Away from the sea there were few inhabitants.

Most of it was considered wilderness.

During the Middle Ages Europe was under a system of feudalism – the land owned by nobility and lived on and worked by peasants who owned nothing. Not even the houses they lived in. In exchange for vowing allegiance to the noble and working the fields, they were allowed to live on the land, for a tax, and grow a small garden for their own use. They could be thrown off at any time, and if they brought any of their own produce to market, they would be taxed on money they received.

Inside greater Sweden, feudalism never got a serious toehold. The aristocrats weren’t interested in owning land that had no value. As subjects of the Swedish Empire, the Finns were legally entitled to the protections that all citizens had. However, the Swedes considered them primitive and their language inferior. They were thought of as a “conquered” people and thus not necessarily afforded the equality that residents of mainland Sweden enjoyed.

Their money was good, however. Because of its undeveloped nature, the Finns were generally left alone to own their land to use it as they saw fit. It was like a little country inside of a big country. They grew crops of rye and barley, raised cattle, horses and fowl and were able to hunt and fish to supplement their food. They took surplus to market in the numerous small villages and profits were theirs for the most part.

Some taxes had to be paid to the Crown, but the amounts were not exceedingly difficult to come up with.

As wartime debts piled up the King was faced with a decision on how to replenish the coffers. He could place extra taxes on the farmers and other peasants that resided across the Gulf. But that would be unpopular and might spark as many troubles at home as he had outside his borders.

Instead, he developed a decree that was similar to our own Homestead Act. He would give title to land in the wilderness to people who were willing to clear the land and build farms where there had been none. More farms meant more tax revenue.

“Workable farms could be taxed, idle hands in the wilderness could not.” Not all land was created equal, and some hectares were more difficult to till than others. Finns became adept at turning “rock farms” into sustainable fields of productivity.

It also made for a different kind of society than was seen throughout most of the rest of Europe. As the world moved on from Medieval times, more private land belonged to families. In Europe, having property was important in many respects. It was valuable, it provided sustenance and income and respectability.

Farmers tended to have large families, and the small farms could not sustain generations of people. By custom and in some cases law, the oldest son was the inheritor of the property. Daughters were married off or left home to become domestics. Other sons had to find their own way in the world, often hiring out as laborers on other farms or as apprentices in carpentry or blacksmithing or as coopers.

For over a hundred years, the Finns had a different opportunity. The oldest son of a farmer still would inherit the family farm, but other sons could petition the Crown for land in the wilderness and start their own farm. This added to an independence few others in the world could enjoy – owning land. It also shaped a society built around a people who, left to themselves, were generally happy and willing to work hard to maintain their way of life.

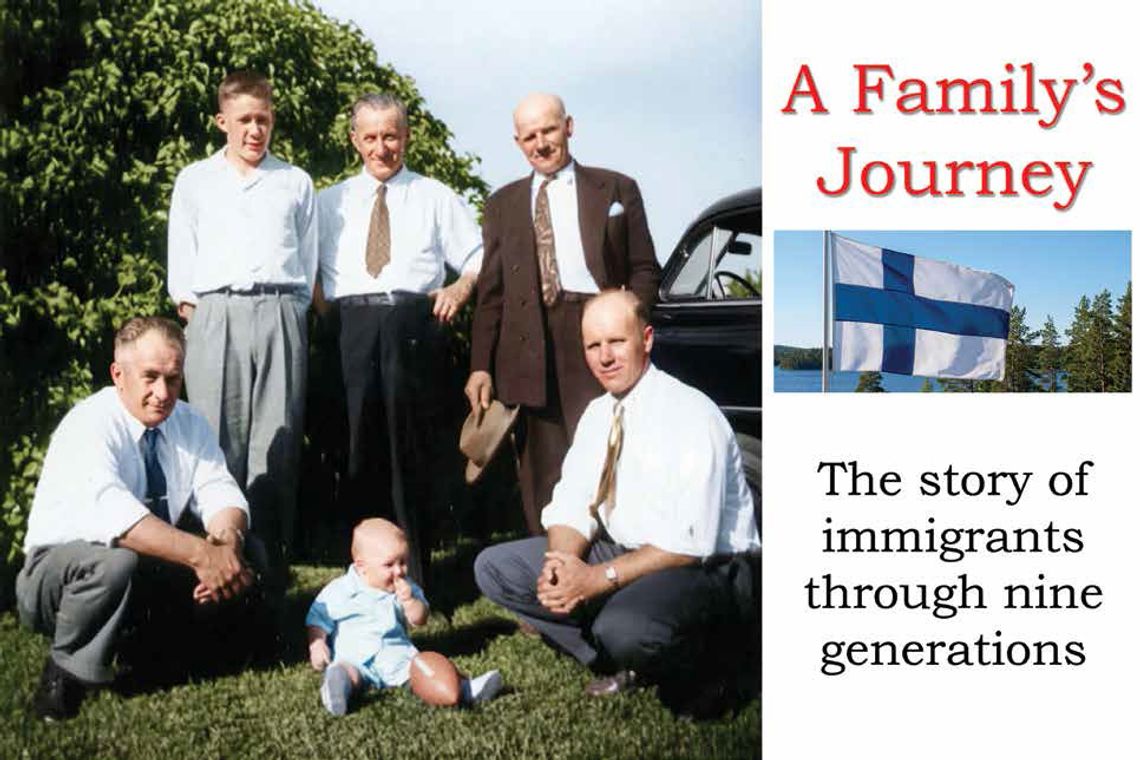

Except for short periods when some of the noble class would change laws or the order of doing business, Finns were left mostly to themselves. Some changes – both good and bad – started to take place in the middle 1600s. It is also where our story of “A Family’s Journey” begins.

Religion affiliation became a big factor. Traditionally Catholic, the Swedes quite rapidly changed to Protestantism in the 1630s. The new leaders of the Church demanded universal literacy within the kingdom. “An illiterate man could never become a full member of the Swedish Church.” Education was not only offered, it was insisted upon.

The Reformation started a lot of turmoil around Europe that constantly simmered and occasionally boiled over.

Sweden seemed to be constantly at war with somebody. Russia was the largest antagonist. Small battles, wars and treaties were fought and hashed out from the middle 1600s until 1809, with each chapter carving a bit more from Sweden’s hold on Finland.

For a while the Swedish Crown enticed the Finns with more freedom of speech and religion to encourage them to stay within the kingdom.

That didn’t last long and soon the Russians were promising to rid the Finns of Swedish oppression by making promises of their own. All the while, Sweden was becoming weaker and a war between the two giants finally ended in 1809 with all of Finland being ceded to Russia.

Tapani Vilppo was born near Ikaalinen, Finland – right in the middle of the central lakes country and right in the middle of seventeenth century political upheavals.

Being the second son, he moved from the farm to the village and became a carpenter’s apprentice. He married and had his first son, Juho.

Wanting a life better life for his family, he moved to an area several kilometers away and petitioned the Crown for a piece of land along a lake by the name of Kuivasjärvi.

In Finnish, a point of land that extends into a body of water is called a “niemi.”

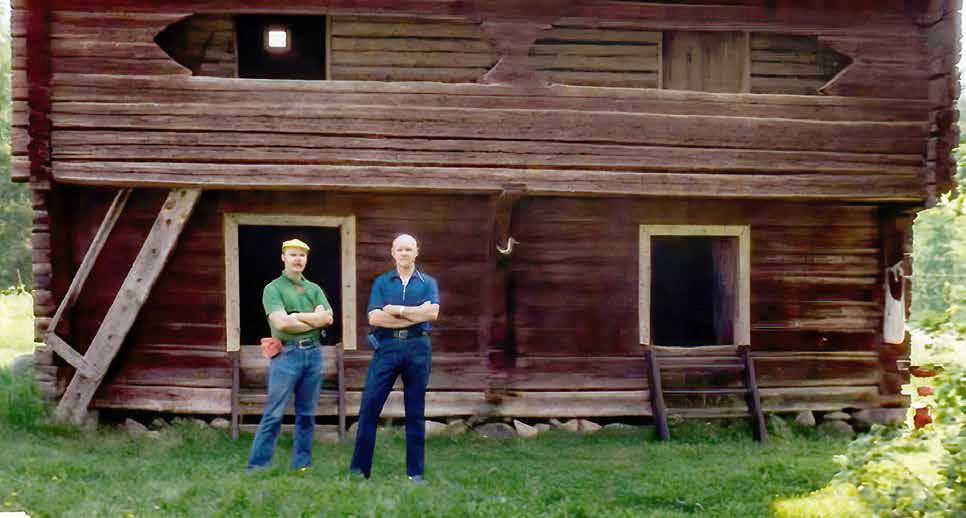

With the work that had to be done clearing the land from forest to a workable farm, he decided to name his farm Kirvisniemi, which translates into English as “axe peninsula.”

Tapani was my eighth direct ancestor.

Next time: Chapter 2 – A Migrant Population